Twenty years ago, the National Black Marathoners Association (NBMA) started what we like to refer to as the third running boom — ethnic minorities, a movement that has certainly financially benefited race organizers and run specialty retailers and brands by introducing this underrepresented market segment into the sport.

Based on our 2010 marathon study, Blacks represented about 16 percent of the U.S. population, but less than one percent of marathon finishers. The percentage of African American finishers at other distances wasn’t much higher. This 15 percent gap between Blacks in the U.S. population and the running community represents a huge growth opportunity for retailers and brands.

The NBMA has embarked on training and education programs to close this gap. The running industry noticed the success of these programs as the number of African American distance runners, clubs and crews increased. Due to the “curb cut effect,” the NBMA paved the way for other ethnic minorities to form similar national supportive organizations, such as Black Girls Run (2009) and Black Men Run (2013) and Latinas Run (2016). The founders of some of these organizations were NBMA members. Financial support for the NBMA from race organizers, running retailers and brands is needed to continue this growth.

The Running Booms and NBMA

“What is not defined cannot be measured. What is not measured, cannot be improved. What is not improved, is always degraded.” So said physicist and mathematician William Thomson Kelvin.

A case history of the running booms and how they were measured and then marketed is illustrative of what can be happening now with the NBMA.

Recall that the first running boom started in the 1970s and encouraged men to pursue healthy lifestyles through physical fitness activities, such as jogging. Then the second running boom, which focused on women, was organic and occurred in the 1980s. The men took women (i.e. wives, daughters, mothers, etc.) to races. Also, the races (and club training runs) went through the White communities. Thus, women were passively given first-hand exposure to distance running. They didn’t have to travel far to be inspired or to find role models.

Measuring and monitoring the growth of women runners was unintentional. The data were tracked and measured through race registration forms, where gender identification was required for distributing awards. Initially, this data were not captured for marketing.

When the running industry noticed the growth and economic potential of women runners, they invested money to attract and grow this market segment. The races switched from offering unisex finisher shirts to gender-specific shirts in different styles and colors. Brands started developing woman-specific product lines, such as sports bras and shoes. The race cut-off times were increased, which opened the doors for more women participants. And more women were appearing in promotional and marketing materials. As a result of the attention given to this marketing segment, women represent about sixty percent of race finishers.

It’s important to note that these changes only occurred because gender was being identified and tracked on race applications. That’s where the NBMA, which has been promoting the inclusion of race/ethnicity on race applications for 20 years, gets involved. We felt that if the running industry saw the growth of ethnic minorities, they might financially invest in our programs to accelerate the growth of this market segment.

Unfortunately, unlike the women’s running boom, the ethnic minority boom would not be organic due to myths, nonexistent role models, few distance running coaches and the lack of races and training routes through the Black communities. The NBMA developed and implemented programs to address these challenges.

The NBMA, a nonprofit entity, started in 2004 as the country’s only national Black running organization. Although “marathon” is part our name, we have always been open to runners of all distances. In 2004, the two co-founders, myself (Tony Reed, executive director) and Charlotte Simmons were experienced runners. We had completed more than 200 road races, including more than 70 marathons combined. We also had previous experiences as members or officers of our local running clubs in Atlanta and Dallas. We understood the running community.

Mythbusting Black Runners

The NBMA’s three objectives are to:

• Encourage people to pursue a healthy lifestyle.

• Recognize the accomplishments of African American distance runners.

• Provide college scholarships. (Over $50,000 has been awarded.)

The first two objectives are intertwined. Unlike the second boom where role models were easily accessible, the community was supportive and races were routed through their communities, we had to find and promote African American role models in our communities and proactively become MythBusters. The major myths are twofold:

1. Running is bad for your knees.

2. African Americans are sprinters, not distance runners.

The first myth was addressed by encouraging African Americans to obtain their Road Runners’ Club of America (RRCA) Distance Running Coach Certification. In 2015, the NBMA partnered with the Dallas Marathon and the RRCA to award scholarships for this certification workshop.

Based on the positive feedback and social media attention, the number of Blacks who obtained their coaching certification exploded. This set the standard and other national Black running organizations began pursuing coaching certifications for their ambassadors and running leaders. These coaches were able to implement “couch to 5K” programs and, later, half marathon and marathon training programs for African Americans, while teaching injury-prevention strategies.

They also partnered with local retailers and fitness centers to offer workshops on topics, including running shoe selection, proper bra sizing and fitting, strength training and stretching.

The second myth about African Americans only being sprinters led the NBMA to create a biennial awards occasion — the National Black Distance Running Hall of Fame and Achievement Awards Event. This was about recognizing the accomplishments of overlooked distance runners, while building a portfolio of role models for future runners. For example, people are only recently acknowledging that Ted Corbitt conceived of changing the NYC Marathon route from multiple loops in Central Park to running through the five boroughs. Inductees were, subsequently, recognized by other halls of fame and athletic organizations.

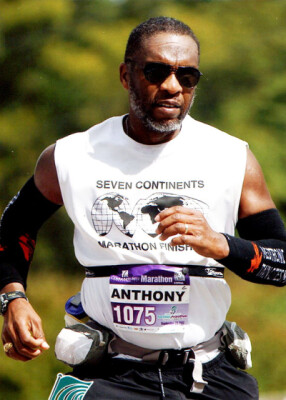

In 1982, at the starting line of my first of 132 marathons, the White runners told me that I was in the wrong race and they were discouraging me from participating. However, as my family’s genealogist and as student of a Black history, I focused on my Black “myth busting” role models, Benjamin Coleman and Dick Gregory. In 2007, I became the first Black in the world to complete marathons on all seven continents.

My running clothes and other artifacts from the last continent, Africa, are with the Smithsonian Museum of African American History and Culture and a special three-hour video recording of my life story is in the U.S. Library of Congress. In 2013, I also completed marathons in each of the 50 states. In 2022, the RRCA inducted me into the National Distance Running Hall of Fame.

If I had listened to the 1982 naysayers, instead of focusing on my role models, my accomplishments may not have occurred.

Recognizing Black Runners

The biennial awards event also recognizes the achievements of “ordinary runners, who have completed extraordinary goals” such as:

• Marathons or half marathons in 50 states, seven continents or Five Island Challenge

• World Marathon Majors

• One hundred or more marathons or half marathons

• Three or more Boston Marathons, where they met the qualifying times

• Ten or more 140.6-mile triathlon (minimum of 2.4-mile swim, 112-mile bicycle ride and 26.2-mile run)

Based on our research, many individuals did not pursue and/or achieve these goals until after we promoted the goal, they read it on our website’s Achiever’s webpage or they met a NBMA member at our summits who had reached the goal.

NBMA documentaries and their related shorts were selected by 28 film festivals in the U.S., Canada, Sweden, France and India. They’ve received 29 awards, including 14 first place awards. More importantly, they’ve had major impacts on the Black running community.

In 2015, our official historian, Gary Corbitt, began compiling the names of the fastest African American women marathoners. A person inquired about the fastest U.S.-born, African American women marathoners. The latter became known as “The List” in the Black running community. Marilyn Bevans, who was inducted into the first Hall of Fame class, was also the first to achieve this feat at the 1975 Boston Marathon. During the next 45 years since 1975, The List had grown to about 20 women.

To encourage more U.S.-born African Americans to pursue this goal, I wrote and directed the documentary, titled Breaking Three Hours: Trailblazing African American Women Marathoners. It profiled nine of our Hall of Fame inductees. Within two years, 10 more U.S.-born Black women achieved this goal, compared to only 20 women over the previous 45 years. This goal of making The List has become the new standard for the serious Black women marathoners. Their next goal is qualifying for and competing in the U.S. Olympic Trials. According to mathematician William Thomson Kelvin, we defined it, we measured it and we improved it.

Our current documentary project is titled We ARE Distance Runners: Untold Stories of African American Athletes. It focuses on dispelling the myth that African Americans are sprinters, not distance runners. This features six Hall of Fame inductees who went from inner city poverty to making world history, running more than 3500 miles from Los Angeles to New York City, setting world records, overcoming breast cancer, losing more than 100 pounds and coaching more than 30,000 runners. This movie is still in the film festival phase and needs your support for completion.

Run Specialty Opportunity

Since 2004, the NBMA bought the seeds, planted them, purchased and applied the fertilizer and paid the water bill for the crops. Then run specialty retailers, race organizers and brands harvested and benefitted from the crops.

Unfortunately, the industry did not financially invest in the programs. Our programs started the ethnic minority running boom. However, we need the running industry’s tax deductible financial support to implement the next phase of our educational programs, to reach more African Americans and make the industry more profitable.